Games for Cities

#1Circular City / Amsterdam

Amsterdam

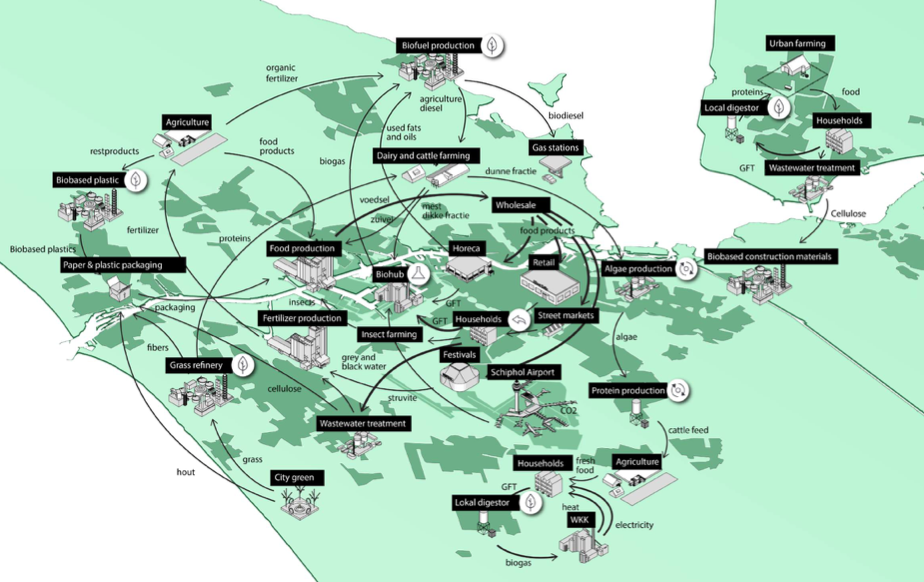

As an engaged citizen of Amsterdam, you care deeply about what goes on in your city, especially in your immediate neighborhood. Recently, the City of Amsterdam has expressed its desire to become one of the world’s first circular cities and in many respects seems to be well on its way to reaching this goal. Ambitious reports are being published and “circularity” quickly seems to be becoming the new buzz-word. Within this hype, the municipality is repeatedly calling for broader participation: there is no circularity without collaboration.

As impressive as this all sounds, however, the circular economy is complex and you struggle with the complicated technical jargon. What does it actually mean to be living in a circular city or in a circular neighborhood? And how can you, the engaged citizen, not only stay informed of this development but also actively participate? How can you best optimise your role and become an effective link in the chain that will ensure the growth and success of the circular city?

This situation drove us to formulate The Circular City Challenge. With you and your communities’ interests in mind, we ask:

HOW CAN GAMES ENGAGE LOCAL RESIDENTS AND ACTIVATE THEIR PARTICIPATION IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY?

As a method which easily allows the participation of a large number and wide range of players, gaming has its role to play in meeting this challenge. Gaming is well-known for its ability to distil complex information into accessible formats and can thus be used effectively to distribute knowledge and raise awareness. Moreover, as an inherently participatory and immersive experience, gaming has the potential to activate residents’ sense of ownership as well as their agency in impacting the spaces around them.

We tackled Amsterdam’s Circular City Challenge through the following events:

Event #1

The Circular City-Game Jam

During The Circular City-Game Jam, a total of 5 interdisciplinary teams (consisting of designers and researchers) worked together with local entrepreneurs and design experts in Amsterdam to create five city-game prototypes that tackle the 5 issues listed below.

This City-Game Jam was part of the Games for Cities Training School program, organised in collaboration with CyberParks, Amsterdam’s University of Applied Sciences Lectorate Play and Civic Media, and Utrecht University’s New Media Studies Department. The specific focus of this Game Jam was to create city-games that can be played in public urban areas as a direct means of engaging local citizens on the circular use of organic waste materials.

As an introduction to this concept of circularity, and to games as a medium for encouraging greater collaboration between participants, Play the City’s ‘A Circular Amsterdam Game’ was played to get the juices flowing. This was a great icebreaker at the start of an intense week of learning and designing, where genuine collaboration between students was both an essential part of the game, and of later game design progress which continued throughout the week. On top of this, the game facilitated the development of a common vocabulary for engaging multiple skill-sets and knowledge bases around a common issue – circularity.

These are the 5 cases that students worked on in their game designs:

1) Wastedlab – A Plastic Recycling initiative in Amsterdam-Noord: A city-game that enhances the effectiveness and capacity of the current recycling strategy.

2) Prospecting the Urban Mines of Amsterdam: A city-game that makes a start on an urban mining strategy for a more circular use of building materials in Amsterdam.

3) Noordoogst: A city-game that promotes the development of unexpected partnerships and circularity loops in the Noordoogst community, specifically regarding organic wastes.

4) Air pollution in Amsterdam: A city-game that promotes citizen awareness and action regarding air pollution, particularly connected to vehicle emissions.

5) Urban water in a changing climate: A city-game that helps build and support a bottom-up approach to water management to support top-down approaches.

Event #2

The Circular City-Game Talk Show

The Circular City Talk Show followed up on the Game Jam to provide a platform for the 5 design teams to develop their game prototypes. Moreover, the Talk Show hosted a number of distinguished local and international city-gaming experts to discuss the role that serious gaming can play in creating more circular cities.

Master of Ceremonies:

Michiel de Lange_Assistant Professor in New Media Studies, Department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University, and co-founder of The Mobile City

Speakers:

Lucy Chamberlin_RSA, London

Ilaria Mariani_Politecnico di Milano, Milan

Kars Alfrink_Hubbub, Utrecht

Francesca Miazzo_Wastedlab, Amsterdam-Noord

Maarten Mulder_HvA, Amsterdam

The Talk Show was open to the public and took place at Pakhuis De Zwijger. Invited speakers presented their work, and their various design challenges, to attendees. Following this, a talk-show style debate was initiated between invited speakers and the Master of Ceremonies, tackling questions posed to them by members of the audience.

Event #3

The Circular City-Game Prototype Presentations

Sharp minds presented their game design research and proposals for facilitating the improvement of some circular initiatives already underway in Amsterdam.

This was the culmination of a week long programme bringing game designers and postgraduate students together to discuss the potential for games to facilitate the development of more circular cities. This desire has been expressed by the City of Amsterdam, which aims to be one of the world’s first circular cities. Circularity requires collaborative solutions – so the question is then extended to whether games – which are inherently participatory and immersive – can facilitate this need for broader participation and engagement. During the previous week, 20 handpicked students from a variety of disciplines and Universities around Europe, were divided into 5 groups – with each group assigned a micro-scale circular initiative currently taking place in Amsterdam. The challenge is to investigate the potential for games to improve the success of each of these initiatives, which these students then presenting their findings and recommendations on.

The 5 game prototypes are discussed below:

1) Funplastic: A city-game that promotes plastic recycling (Wasted).

‘Funplastic’ starts with the premise that current plastic recycling efforts initiated by Wastedlab are less effective than it could potentially be, as a result of various stages in the recycling process being precluded from the public’s view. Current recycling strategies are too ‘linear’, requiring the public to provide the inputs for recycling without making the outputs visible. It was decided that this has a counter-intuitive logic, where the public’s recycling behaviour is not positively reinforced through visible, functional and valuable outputs. Another point of departure was to move away from recycled products which require added energy to produce, and towards re-used products. The game targeted children specifically, with the hope that parents and family members would follow. The narrative includes a ‘waste-monster’ who has been ‘stealing’ the city’s plastic (an activity that we’ve been aiding him/her in for generations without ever thinking critically about it). But now this monster has left a trail of plastic for us to find him/her. Children are encouraged to follow these trails that have been left all round the neighbourhood, until they reach the public square where they find that the ‘monster’ has actually been making things with the plastic all this time. This provides inspiration to kids who are invited to participate and make their own plastic products. This might entail receiving inventory lists and manuals for making certain items, imploring children to collect enough items of plastic to ‘buy them entry’ to the building park. Collaboration with friends is encouraged to make the collection process for each person easier. On this ‘launch’ day, a boat race will be staged between residents of Amsterdam and Amsterdam-Noord, linking the two areas and metaphorically ‘closing the loop’. This launch is intended to attract the attention of the wider public who might be inclined to participate in the fun of recycling. The result is an ever-changing open-air museum of plastic products that is flexible to manipulation by kids and therefore encourages a sense of ownership, and which functions as a marketing image for the city of Amsterdam.

2) MetalKong: A city-game that sets out with the ambition of adding social and cultural layers to an urban mining strategy for Amsterdam.

‘MetalKong’, designed by the Game Bommm team, builds onto data that has been captured for Amsterdam concerning the presence of valuable recyclable metals in the city of Amsterdam. One potential use of this data might include the future extraction of these valuable materials from buildings (from a previous construction era), replacing them with newer material technologies. The Game Bommm team felt that limiting the research to the physical presence and monetary value of these materials failed to acknowledge the social and cultural values attached to these buildings. The goal of this game was to raise awareness about the resources that can be recycled in buildings, and to harvest social sentiment data connected to this. The designers made a 30 minute event of an Augmented Reality mobile game with players walking past buildings. MetalKong – a huge ape – is on a rampage and metal is needed to build a cage. Players have to locate buildings that hold resources and grade them on a social use scale. After finding them all they can decide to recycle them, thus destroying the building and adding to the cage. Or they retain the building for social reasons but thus risking MetalKong’s release. This game implicitly also gathers data about citizen’s reaction to urban mining. It thus uses a second step to drive home their message. This game plugs into the ‘virtual’ urban exploration game model hype, gaining popularity because it’s just so fun and ‘in’ at the moment. This would allow data analysts working for the City to discover whether buildings with social and cultural value ascribed to them actually increase the real value of these buildings beyond being worthy of recycling its building materials. A game that captures important datasets through making participation fun, flexible, and self-directed.

3) Food loop: A city-game that encourages players to learn more about circular organic waste flows in the Noordoogst community of Amsterdam.

The team’s point of departure was that peoples’ knowledge of circular organic waste flows is generally quite limited. They thus set out with the objective of designing a game that would educate players on how organic wastes available in the Noordoogst community could be re-used as inputs for other processes. The game is primarily aimed at kids, educating from the ground up so-to-speak. In the game, players must match outputs with inputs to create circular loops. When a correct match is made, the player is alerted by a sound, and the same goes for incorrect matches. The game can can be played on a physical board for the first few levels, however, this limits the potential for further learning in the game for those who are interested. An app was the solution, allowing for exponential scalability in the complexity of food loops and the learning potential for players, with difficulty increasing as players move through the levels. Connecting the right waste product to the recycler will complete levels. Each level is a more complex version of the circular economy, and therewith closer to reality. The physical formation of the loops and the incremental learning make this complex system tangible.

4) CarZilla: A city-game that promotes citizen awareness and action regarding air pollution, particularly connected to vehicle emissions.

‘CarZilla’ starts with the objective of making air quality in Amsterdam everyones business – to make everyone conscious of the issue so that they can each take action in their own lives. This takes on an awareness raising strategy for the game, with follow up games to encourage genuine action. The team visited Amsterdam’s most polluted intersection, where Valkenburgerstraat meets Weesperstraat, and noted that cars moved predominantly in one direction (North-South), while bicycles moved in the other (East-West). They decided to design a playful interaction with 45 seconds being the time in which they could engage either cyclists or car drivers while they were stopped at a traffic light, using the material affordances of the space. On a polluted crossing bikers and car drivers compete for the safety of the city. Carzilla is forcing car drivers to pollute the city. As the bikers approach the traffic light, their bike lane alerts them of the imminent choice: do they take a stand against air pollution (group left/green), or don’t they (group right/red). Opposite of the light is a display showing Carzilla’s health. Every car passing will power him up. Every biker on the left will whittle him down. Making use of the shared materiality, this game creates an aware community in a very short time. 45 seconds later, the game is over and a new set of players arrive at the intersection. While this playful interaction is pitched at raising awareness, the team hope that players, and observers, exposed to this playful learning could decide to switch to greener mobility choices in reality.

5) contRAINer: A city-game that helps build and support a bottom-up approach to water management to support top-down approaches.

‘contRAINer’ is a rain collection shelter that encourages playful learning. The aim was to encourage citizens to become more involved in their own water management strategies in a changing climate. The team decided to create playful installations, surrounding, and using, water as key instruments in their installation mechanics and functions. For example, a swing that is designed to pump water from low-lying potential flood areas to areas of water capture or retention. Oosterpark was chosen as a potential site for the first installation, as it is a park that attracts a wide diversity of users, both from the area and surrounding ones in Amsterdam’s city centre. The general idea in making water a prominent feature in these installations, is to get people ‘thinking about water’, and to make this learning fun. Depending on the interaction with a series of levers and a swing, the water could either overflow (no action), drain (individual action), or water some flowers (collaborative action). The installation relies on facilitating debate and procedural awareness.

Some lessons learnt:

This first game jam in the Games for Cities programme ultimately generated five key insights into some considerations for city-game development:

1. Addressing an urban issue through a game requires a difficult balance between the two. Often the problem and approaches are clear, but how to gamify it isn’t.

2. Games must function in an urban context, replete with stakeholders and projects. Games can then serve to highlight unenlightened aspects of existing projects.

3. The urban space of play is a great source of material design. The setting provides the physical circumstances and the goal. The mission is to fit the game to the actors involved.

4. Games can explain complex systems in a variety of ways, ranging from filtered simplifications to incremental and procedural versions bordering on reality.

5. Conveying a complex message is often an iterative and sustained project.